History of ISA

The story of the International School of Amsterdam is a children’s story. It is the story of the many hundreds of high-spirited, colourful young personalities from around the world who have passed through the school’s corridors and classrooms during its first half century. It is the story of those children seeking to fulfil their educational potential.

It is the story, too, of their families and concerned corporations and diplomatic missions; it is the story of a long line of distinguished, public-spirited individuals, Dutch and foreign, who have served on the Board and in the Parent-Teacher Association; and it is the story of an exceptionally diverse group of experienced teachers and administrators who have shaped and reshaped the school’s programmes to meet a changing community’s changing needs.

The story of the International School of Amsterdam is a story with a context. It belongs to the rich, larger history of the great city of Amsterdam itself, to the history of a post-war world, and to the late twentieth-century history of an emerging Europe and an increasingly global international society.

The story of the International School of Amsterdam is a story of the pursuit of excellence, knowledge, truth, and humanity, a story of each participant’s endeavour to achieve his or her personal best. It is a story of the abiding values associated with basic skills and a liberal education in the arts and sciences. It is a story of cooperation between many people from many nations and stations in life endeavouring to meet a practical need for the education of the young in a world on the move.

The Earliest Historical Accounts

Questionnaires were circulated among the international business firms in the Netherlands in the early 1950s in an attempt “to pinpoint problems faced by international businesses and businessmen in the Netherlands. The results of those questionnaires uniformly revealed that the No. 1 problem was that of educating their children”. Because the vast majority of international businessmen were posted abroad for a period of just one to four years, “the availability of excellent Dutch language schooling … could provide no real solution”. Moreover, the survey concluded, the influx of large numbers of foreign-language students “could only be disruptive to the Dutch system, thus providing no satisfaction to either the foreign or Dutch communities”.

According to an article in The Brussels Times in 1965 (the year after the International School of Amsterdam opened), there had been 18,739 registered non-Dutch nationals residing in Amsterdam, a city with a population of 866,000. Of these, 1,031 were British, 723 were American, and 180 were Canadian. The only educational choices expatriate families had were to send their children to local Dutch schools or else on an intolerably long journey to English-language schools in The Hague. It was for this reason that Mr. A. Uyttenbroek, a director of IBM-Netherlands, decided to help establish an international school in Amsterdam.

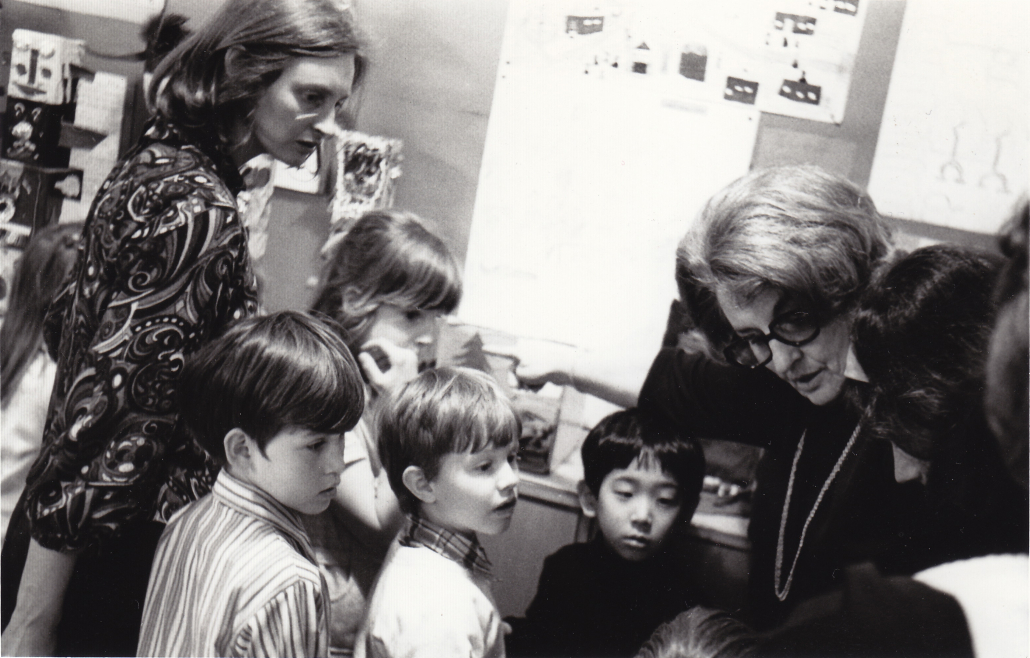

The International School of Amsterdam “opened its doors in January 1964 to admit one pupil, a five-year-old English girl, Eleanor Maclean. English teacher, Mrs. J. Rigby, was appointed to start the school, and by the end of the first term there were two additional part-time teachers, Mrs. Rombach and Miss Cox, and 13 students”.

Crucial for Amsterdam

The International School of Amsterdam was established towards the end of the unique period of American world leadership that followed World War ll. President Eisenhower’s restraint and President Kennedy’s idealism and successful space program, when added to the American contribution to the liberation and reconstruction of Europe, had earned the United States great respect, especially amongst the older generation, who generally accepted and valued the American role in the world. By the 1960s, the hard years of immediate post-war recovery had been superseded by a period of economic growth and booming international investment. There was a new prosperity.

Many international businesses of many nations were confronted by the need to provide their highly mobile executive families with suitable educational opportunities for their children. Hence, corporate leaders often took the initiative in establishing international schools, as in Amsterdam. Leading members of the worlds of business, diplomacy, and education came together to solve a practical problem, which was in fact a global problem with some interesting local variations, as in the Netherlands. The Hague had become the most active centre in providing American schooling, largely because of the large [numbers of] diplomatic and military personnel stationed there at the time. The availability of English-language schooling had led the commercial community “to give preference to The Hague in the establishment of their Dutch- or European-based subsidiaries or offices.”

Thus the establishment of ISA had been important, even crucial, for the commercial development of Amsterdam. Among other points, the availability of ISA was “one of the reasons why the city of Amsterdam was favored over other locations as a center for Japanese business activity in Europe”.

While many had attempted to establish an English-language international school in Amsterdam, it was not until 1964, through the energetic and persuasive activity of Mr. A. Uyttenbroek, then Managing Director of IBM, that the Mayor and key municipal officials of the City of Amsterdam agreed to the establishment of an International School, and two rooms of an existing Dutch school at Winterdijkstraat 8 were made available to this end. “The timetable included arithmetic, reading, writing, scripture, and art in the first grade”. In the higher grades, pupils studied English, social studies, general science, and French. Physical training was taken “with the corresponding grades in the Dutch school”, and there were handicraft classes “for the girls”.

The principal by now was Mrs. Dorothy Vincent. There were 117 pupils from 16 countries, nine grades, and six additional classrooms at 77 Vechtstraat. Special instruction was provided for non English-speaking children, and there was an extra-curricular course in Japanese “for the increasing number of that country’s children whose fathers have set up businesses in North Holland”. Employees of over 60 different international firms had sent their children to the school since it opened.

The Challenges of Growth

The year was 1971, and ISA had 175 students – 24 of whom were Japanese – 18 teachers, and expectations of future growth. ISA offered grades K through 10 and was considering adding grades 11 and 12 to create a full high school. Prospective growth and the services made available would depend on enlarged facilities, which only the city could provide.

A Board memorandum noted, “As an illustration of our predicament, we are presently being advised that at least one large American company plans to bring more than 40 families to Holland this coming June [1972] and that they prefer making Amsterdam their prime commercial focus”.

In fact, Texas Instruments did come to Amsterdam to contribute to the opening up of the North Sea oil fields. Teachers who were on the staff at the time can recall that, for just two years, the school took on an American Southern drawl – a real challenge to the British tutors favored by Mrs. Vincent, especially for the younger children.

At the beginning of the 1972-1973 school year, the Mayor and Aldermen of the city enabled ISA to move from its classrooms in the Winterdijkstraat and Vechtstraat to five, clearly temporary, wooden, four-classroom buildings, inelegant but cozy, in a park-like environment on the Meer en Vaart in Amsterdam-Osdorp. In March 1977, ISA moved to more purpose-built facilities, across the street from the Free University, at 875 A. J. Ernststraat in Amsterdam-Buitenveldert.

Mayor Samkalden, long an honorary member of the Board, attended the dedication ceremonies held in the Great Hall on Monday, 4 April 1977, together with many ambassadors and businessmen. Teachers and students served as hosts and escorts for the distinguished guests.

The Meaning of International

Just what “international” should mean may be a subject of debate between pragmatists and idealists. What it has actually meant in the history of the lnternational School of Amsterdam can be a matter of historical description. It is clear that the term has meant different things to different members of the school community through the years of the institution’s evolution. To most, it has meant simply that ISA is the place where their family members have met people from other countries and where their children have studied together and become friends before returning to Stockholm, Belgrade, Karachi, Houston, Rio, or Tokyo. To some others, the term has invoked a utopian future order in which all the world’s peoples will be one, as modelled now by the children of diverse cultures gathered in the classrooms of the “international” school, engaged peacefully in common activities – a future world order to be worked towards by using the world’s international schools as a wedge.

Just as profound are the encounters between cultures at an international school. The world’s religions, ideologies, and lobbies meet in its classrooms and on its committees. Sceptics and believers, evangelicals and ecumenists, Moslems and Hindus, Catholics and Jews, Buddhists and humanists, Protestants and Marxists, intelligence officers and renegades, royalty and merchants, scientists and athletes, actresses and bankers, diplomats and gamblers, people of the day and people of the night, the sons of Asia and the daughters of the Occident, reds and greens and yellows and true blues – all shoulder together the task of banning illiteracy and innumeracy from their homes by providing each child with simple, basic skills and some universal values. One plus one is two. Wash behind your ears. Button up your coat. Tell the truth. Learn how to spell “Mediterranean Sea” and “Tiananmen Square.” Develop your keyboard skills. Consider Sophocles and Salman Rushdie. Check out the etymologies of “assassin” and “sputnik”, “glasnost” and “berserk”. Locate your family’s place in the taxonomic nomenclature. Learn to say no. Try out for the team.

There is a great deal that international families can work on together.

Excerpt from History of ISA – Donald Morton (2002)

Contact Us

Sportlaan 45, 1185 TB Amstelveen, The Netherlands

Telephone: +31 20 347 1111

Fax: +31 20 347 1222